“If you want to be a writer, you must do two things above all others: read a lot and write a lot.”

Stephen King, On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft

In On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft, author Stephen King recounts being sick during most of first grade. Bedridden and housebound most of that school year, he filled his time by reading “approximately six tons of comic books.” He ultimately began writing his own stories, incorporating those comics “word for word…sometimes adding my own descriptions where they seemed appropriate.” One audience for his “copycat hybrids” was his mother, who celebrated those stories, but also encouraged him to write a story entirely his own. His first attempt at doing so was a 4-pager about a large, white bunny who can drive. When he read it to his mother, King said he could tell she liked it because “she laughed in all the right places.”

Prolific author Dav Pilkey relates quite a different experience in his early writing ventures—being disruptive in class, he spent most school days sitting in the hallway. In second grade, he spent his daily hallway stints creating his own original comic book about a superhero named “Captain Underpants.” His teacher wasn’t impressed and ripped it up, telling him “he couldn’t spend the rest of his life making silly books.” Fortunately, Dav “was not a very good listener.”

What a very different reception to their early writing attempts these young writers had!

In How to Become a Better Writing Teacher (2024), educators Carl Anderson and Matt Glover name response as one of the guiding principles of writing instruction. “Students need teaching that responds to their needs as writers.” This teaching includes both conferring with writers and whole and small lessons—lessons whose instructional content is determined by what writers need to learn. Responsiveness means embracing the need for writers to talk to other writers about their drafts as well as establishing ways to share published writing. It’s the responses of audiences who matter to them, such as King’s mother, that allow children to “experience writing as a communicative act” (Anderson and Glover, 2024).

In our fiction writing unit, my students chose either to invent their own fictional characters or write a story about an existing fictional character. In the classroom story that follows, you’ll meet a delightful 2nd grade writer, Sajche, who crafted his own Dogman story (and offered me important opportunities to be responsive to his needs as a writer).

Into the Classroom

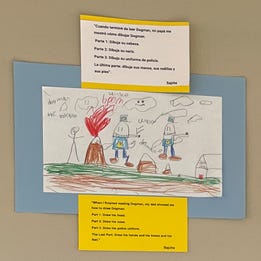

Early in the school year, during the“How We Learn” unit, the class explored how they learned something. Sajche described how his dad helped him learn to draw Dogman.

Sajche loves Dav Pilkey’s Dogman. He’s talks, reads, and writes about this beloved character whenever possible. So when the time came to create his own narrative, Sajche, to no one’s surprise, instantly appointed Dogman as his main character.

During the immersion phase of our writing unit, we revisited several well-known texts already read and discussed. Our purpose: to notice how stories worked. Frank Smith (1988) reminds us, “Teachers must recruit the authors who will become the children’s unwitting collaborators.” Some of the “unwitting collaborators” we re-immersed ourselves in were Dogzilla and The Paperboy by Dav Pilkey, Chrysanthemum by Kevin Henkes, Harold Loves His Woolly Hat by Vern Kousky, Matthew and Tilly by Rebecca C. Jones, and Quiet Please, Owen McPhee by Trudy Ludwig. Because the texts were familiar, the students began to notice a pattern of “writerly” things (Ray, 1999) across the texts. For example, the students noticed how the beginning of stories introduce the characters and setting. While we weren’t reading like writers in the fullest sense yet, we were on our way to noticing and naming some things writers can do.

After a couple of days immersing ourselves in our mentor texts but not yet putting pencil to paper, the students were champing at the bit: “Ms. Debra, when can we write our story?” So, on the third day, I modeled writing the initial draft of my own story. Their initial drafts began flowing as the budding authors talked their stories with partners and then headed off to write. Before the workshop ended that day, several students, including Sajche, excitedly pronounced: “I’m done!”

Still excited the next day, Sajche and I met to confer about his story. He launched right into reading the first few lines of his writing: “Here is my story, Ms. Debra. Dogman: Big Fight. Dogman is a hero. He is part dog, part man, and all hero.” I listened closely to determine how best to support him as a writer.

After reading these first couple of lines, Sajche suddenly began to verbalize his story: “Dogman is a police guy and he wears a costume. The top part is a dog and the bottom part is a man. He’s a hero. In the books, he saves the day.” None of this, however, was actually written on his paper.

Sajche then returned to reading his story, introducing two additional characters from the Dogman universe. “This is Sippy Cups and Munchy, the Lunch Bag. They destroying the city because of the Living Spray.” After reading these lines, he again turned to me to tell more of the story that he hadn’t written onto paper. This back-and-forth between reading his writing and telling his story continued as he read the rest of his 2-page draft.

Now I had a decision to make—how could I support this writer, not just make this story better? Like many novice writers, Sajche told more orally to clarify and expound on what was actually written down. Such beginning writers need to condition themselves to reread their writing to determine if what is actually written on the page accurately and completely incorporates the ideas they wish to express.

Starting with his strength, I began, “Sajche, you know a lot about your character, Dogman. When you reread your beginning, you wrote, Dogman is a hero. He is part dog, part man, and all hero. That tells your readers who your character is and begins to help your reader get to know your character.

I continued, “I can tell you know a lot more about your character, too. As you were rereading your story, you stopped reading to tell me more ideas you have about your character. You’ve put some of your ideas in your writing but a lot of your ideas are still in your brain. The other things you want to say about your character, that he’s a police guy and wears a costume, are still in your brain. As a writer, you’ve got to reread your story and ask yourself, did I write all the things I want to say in my story? If you don’t write them in your story, your readers won’t know those ideas when they read your story.”

I could see Sajche staring at his paper with a slight frown. As Sajche felt his story was “done,” I could almost hear his worry: How can I write more in my story when there’s no space? Sajche literally didn’t have physical space to add any of his additional thinking. So I offered, “Sometimes writers need more space on the paper to add to their writing. Let me show you something you can do so you will have space to add all those ideas about your character that are still in your head.”

As I physically cut the beginning lines of Sajche’s story and taped them onto a new sheet of paper, his eyes widened as he realized what I was doing. Voilà—now he had space to add to his writing! His enthusiasm about revising his story was growing along with his smile.

Before Sajche left the conference, he discussed several ideas he wanted to add to his writing as I pointed to the new space on his paper indicating where he could now had space to write those ideas. I took the opportunity again to nudge Sajche to reread as he writes to make sure he includes all the ideas he wants his readers to know. With an animated smile, Sajche headed off to continue writing his Dogman adventures.

The first page of Sajche’s draft after our conference—at the top is the portion I stapled to the new page. The final draft with all his revisions was six pages long.

Teacher decisions that affect the Conditions of Learning

In How to Become a Better Writing Teacher (2024), Carl and Matt discuss the importance of aligning the guiding principles of writing instruction with our actions, the “day-to-day and across-the-year” decisions and practices that make teaching so meaningful for students (which, of course, also happens to nurture the Conditions of Learning). Here are three such decisions:

· Supporting children to make choices as writers. Being able to choose the characters for their stories is important for fiction writers. Being able to write a Dogman story supported Sajche to see himself as a writer; taking responsibility for this important decision strengthened his engagement in his writing process. For young writers, it doesn’t matter if another writer created the character he is writing about. As Stephen King noted in On Writing, “imitation preceded creation” for him; it’s what helped him begin to find his own path as a writer. So why wouldn’t we invite our young writers like Sajche to experience this same opportunity if they choose? Writing workshop is the perfect time for writers to experiment and approximate and experience a response to their efforts that keeps them engaged in learning.

· Learning from other writers. Learning to write from other writers is an empowering experience. When teachers immerse students in familiar texts similar to those students will write, we give students opportunities to notice the “writerly” moves those writers made. Recognizing and adjusting our expectation for what writing looks like during the immersion phase is also important (i.e., it looks more like reading time!). And, when teachers and other students model their own story writing, they are demonstrating their own approximations of what apprentices of the “writing club” think and do (Smith, 1988).

· Teaching the writer, not the writing. When writers share their writing with us, it’s hard not to think how we could make this piece of writing better. But to grow a writer, our responses should teach things about the craft of writing that will support them in their future writing experiences, not just for this particular writing piece. For example, by immersing the kids in familiar texts to notice what other writers do, we show writers a powerful way to learn how to write when they are no longer our students. In reality, every demonstration has the potential to lead to more learning. Sajche’s learning, for instance, to physically “cut and paste” (or tape and staple, to be precise!) in order to add more to his writing led to nearly every student in the class wanting to add pages to their draft. “I’m done” soon became “I want to add more to my story. Can I add more pages to my story?” Membership in the “writing club” is definitely on the rise!

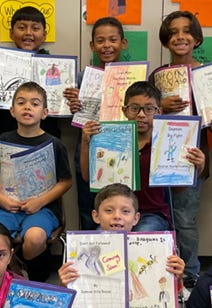

Endy, Santino, Aiden, Gabe, Sajche, and Damian, all apprentices in the “writing club.”

Try This Out

· What choices do you offer your writers across a writing unit? How do those choices support your students as writers?

· How do you immerse your students in models of writing? How do you support them to learn how to “read like a writer?”

· Reflect on some of the conferences you’ve had with students about their writing. Did your response to their writing just make the piece of writing better or did it teach students to be better writers? (This makes for great conversations with colleagues!)

· With your colleagues, examine some student writing. What might you say to teach the writer, not the writing? (Again, a great professional learning opportunity with your colleagues!)

Thanks, Matt! And thanks as well for hosting the book club with Carl and Matt. I've so appreciated the conversations you've arranged for all of us to have.

You have some proud authors in these images, Debra. Thank you for making the decision to nurture their identities as writers.