Thinking Alongside a Budding Writer

(with Guest Brian Cambourne)

Facilitating thinking is more a matter of attitude than of lesson plans.

Frank Smith, To Think

In To Think, Frank Smith (1990) noted that learning to think “depends on the way we perceive ourselves, which depends in turn on the way other people treat us.” The more we associate with others who think, the more we see ourselves as a thinker, which includes, of course, learning to think as readers and writers. Learning to think, Smith says, “depends on the company we keep.”

Expectation, as a Condition of Learning, is about the beliefs we develop as a result of the company we keep. These beliefs have considerable influence on one’s faith in oneself and are powerful coercers of behavior (Crouch & Cambourne, 2020). The view children develop of themselves as learners—the agency Peter Johnston (2012) describes as “a sense that if they act, and act strategically, they can accomplish their goals”—is contingent upon the expectations the teacher has for the learners. As Smith, Cambourne, and Johnston emphasize, the ways in which teachers behave, their language toward students, and the learning experiences they create shape the role children see for themselves in the learning experiences, which, in turn, strengthen the students’ abilities to think.

In addition, these esteemed educators each recognize that the development of a child’s thinking depends upon a certain disposition on the part of the teacher—an attitude characterized by an openness and a willingness to listen to the child and what he or she thinks. Teachers with this disposition, coupled with an appreciation for the need to be responsive, learn alongside children as they invite each child to explore their own thinking. This responsiveness to the learner in turn inspires and encourages responsiveness from the learner.

How does one become a responsive teacher? First, one believes that learners construct knowledge about being literate by actively engaging in purposeful literate behaviors. Teachers with this belief look for regular, authentic opportunities to encourage literacy learning. Second, these teachers have a vision for the looks, sounds, and feels of active literacy exhibited when children are engaging in dynamic literate behaviors. Such vision recognizes and affirms the learners as learners.

All of which leads to a third belief, the necessity of a strong knowledge base for the art and craft of teaching in responsive ways. A teacher’s knowledge base develops within and through the professional communities they are part of. These communities include those we are privileged to teach next door to as well as those whose ideas we learn about through books, blogs, and videos about teaching. Why? Because, as Smith said, everyone’s thinking, including the teacher’s, “depends on the company we keep.”

Into the Classroom

Just like with my third graders, the second graders I’m learning alongside were publishing a self-selected poem at the close of their poetry unit. I was conferring with each poet to ensure their poem was ready for our poetry writing celebration later in the week. Parents were invited and you could sense the students’ excitement in anticipation of sharing their poems.

Matthew, a second grade student, and I sat side by side looking at his self-selected poem on my computer screen. Matthew had written a poem called “My Mom” which began with the words “My mom is so special…” The next lines of his poem shared things Matthew’s mom does to care for him.

After Matthew read his poem aloud, I asked, “Matthew, is there anything you’d like to add or change about your poem?”

He read the poem aloud again, then said, “I really want it to make my mom cry.” He laughingly scrunched his face between his hands in a humorous attempt to imitate a mom crying. “But not a sad cry. You know, like a happy cry.”

Matthew continued confidently, “I want to do something like that 3rd grader. You know…” at which point he left the conference and ran to the front of the room to get the poetry anthology written by the group of 3rd graders I’m teaching. (The third graders had completed their poetry unit a few weeks before and I’d made a copy of their anthology for us to keep in our 2nd grade classroom. It was quite popular during Independent Reading.)

Matthew brought the poetry anthology back to our conference and flipped through the book of poems until he located one written by Cristian, one of the third graders. He quickly ran his finger under the lines as though searching for something specific while he whispered Cristian’s poem aloud. Matthew read, then reread, again almost to himself, the last two lines Cristian had written: My mom is so nice / It touches my heart.

“I want to end my poem like he did,” Matthew said.

I remained silent, giving Matthew space to think. I could feel his poet-wheels turning. After a moment, Matthew rewrote the ending of his own poem, an ending intentionally crafted to elicit happy tears from his mom. His ending includes a deliberate nod to his mentor, Cristian.

Here is Matthew’s poem:

My Mom

My mom is

so special

because

when I’m sick

she takes a lot of care of me

and she always

buys me some stuff

that will make me happy.

And she always feeds me

yummy stuff

She has a good heart and

it touches my heart, too.

Epilogue: I can report that this poem, and the bring-my-mom-to-tears ending, did indeed have the effect Matthew desired. (To say nothing of creating a bring-my-teacher-to-tears moment, too!)

Teacher decisions that affect the Conditions of Learning

Crafting a learning setting which gives rise to the kind of literate behavior Matthew exhibited is built on a teacher’s willing disposition and responsiveness to a budding writer’s process. Here are some decisions that supported this writer’s process.

· Making it ok to use another writer’s words. Some people believe that using another writer’s ideas or words is not allowed; some even think it’s cheating. But this is how Immersion works to support a learner; the role of a mentor is to show possibilities for the learner. As such, a mentor text provides a Demonstration of written elements such as text organization, crafting an introduction, and, yes, word choice. Writers emulate other writers, plain and simple; seeing oneself as a writer, like those we are reading, is a principle of Engagement. Matthew transformed Cristian’s ending to make his own poem affect his audience in a very specific way. Borrowing a few words from another writer and making those words your own is perfectly acceptable.

· Taking time to make their writing public. Publishing means sharing your writing with others and experiencing their Response to the meanings you hope to communicate. Sharing with an audience beyond the teacher, or even classmates, is important. Carl Anderson, during a book study meeting of How to Become a Better Writing Teacher (2024), suggested writers always ask themselves the question, Who are you writing this for? Public sharing makes more sense if you’ve been considering your audience since the initial planning of your writing.

· Bringing in student poetry. We know that adults are not the only teachers in the room (Johnston, 2012). Reading other student’s writing is a powerful way to immerse students in poetry and, in Matthew’s case, allow him to take responsibility for finding his own mentor. In both the 2nd and 3rd grade poetry units I’ve been part of this school year, we have relied on Regie Routman’s Kid’s Poems: Teaching Second (or Third) Graders to Love Writing Poetry (2000) to provide mentor texts. Each of her books, part of a series of grade-specific professional books, incorporates poems written by children in the grade so teachers can immerse students in and demonstrate various aspects of poetry writing. Each poem includes both the hand-written version and the fancy, published one (both of which the kids LOVED!). For second-grader Matthew, third-grader Cristian served as a more-knowledgeable mentor, just as Cristian himself was mentored by other students through the poetry found in Regie’s book. Each of these young writers is learning to think as writers through “the company they keep.”

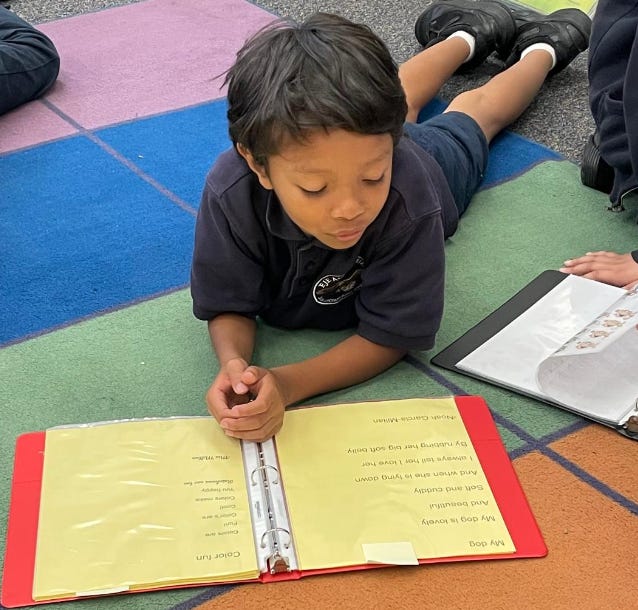

Matthew reading the 3rd grade anthology during Independent Reading time.

Try this out

· What we know as writers we learn from other writers. How do you support your young writers to learn from other writers? Do those writing mentors include other young writers?

· Sharing your writing publicly is such a celebration for writers. What audiences do your students have for their writing? What does publishing look like for your students?

· A learning community is critical if we are to grow as professionals. Who is the “company you keep” to support your own learning?

Thanks, Regie. Being a responsive teacher matters to much to our students. I was thrilled to be a witness to this child's engagement in writing.

A terrific article on how and why applying the conditions of learning and teaching responsively influence and inspire students as critical thinkers, readers, and writers who enthusiastically engage -- in this case--with writing free verse poems with confidence and joy.