Showing What You Know

By looking to the children to teach us what they knew and how they knew it, we saw how to make learning meaningful.

Martha Horn & Mary Ellen Giacobbe, Talking, Drawing, Writing: Lessons for Our Youngest Writers

In Talking, Drawing, Writing: Lessons for Our Youngest Writers (2007), Martha Horn and Mary Ellen Giacobbe remind us the critical roles talking and drawing play in meaning-making.

On talk, the authors reference Vygotsky (1978), stating that “talk is one of the basic symbol systems, along with gestures and drawing, that children use to communicate before they ever put words on paper.” Talk allows children to “use the words they have to say what they know.” Maria Nichols (2019) refers to this as “purposeful talk”—talk whose intention is “to strategize, to innovate, to problem-solve, to construct understanding.” Zaretta Hammond echoes this idea when she speaks of turning and talking as “how we turn information into usable knowledge” (Managing Instructional Change: Summer Planning to Help Teachers Close the Knowing-Doing Gap in the Fall, June 7, 2024).

Drawing, Horn & Giacobbe say, gives children “opportunities to do what writers do: to think, to remember, to get ideas, to observe, and to record” (2007). The authors offer five reasons why drawing is important for young writers. First, drawing is a “primal way that beginning writers represent and understand meaning.” Second, drawing is a “way for children to be heard,” even before they have full control over letters and words. Third, drawing is “a medium through which children can develop language.” As children represent meaning through drawings, they are “processing, composing, and thus developing language.”

Fourth, drawing provides opportunities for children “to go deeper into their stories,” providing additional details to go along with the words they write. And, finally, children learn about the craft of writing as they talk and draw, when what children “learn how to do in one mode sets the stage and supports learning how to it in the others.”

So when we think about creating an optimal learning environment, ensuring children have time for creative responses where they are talking, drawing, and writing about their learning is essential. In the story that follows, a group of second-grade learners have multiple opportunities to talk, draw, and write about science content they are learning.

Into the Classroom

The second-graders were learning about fast and slow changes to the Earth’s surface caused by wind and water and other geologic events such as earthquakes and volcano eruptions. Understanding how volcanoes form and erupt, how landslides occur with often devastating effects, and how canyons form over time were some of the big concepts with which these curious young scientists grappled. (At the end of the unit, they would be expected to write about what they had learned which would be graded for their report cards).

Over the course of several weeks, the students excitedly read and discussed causes and effects of these awe-inspiring wonders. To help students understand and envision these far-removed-from-direct-experience events, they watched and discussed videos that demonstrated the fast and slow effects of water and wind on land and showed volcanoes and earthquakes in action. In addition, they participated in multiple Mystery Science experiments to help them design, create, and observe small-scale models of these large geological occurrences and consider ways to slow or prevent these changes and the resulting effects.

Creating and observing a model of water erosion

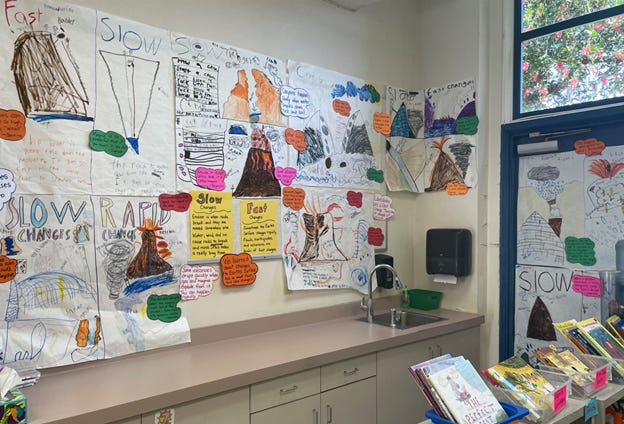

Towards the end of the unit, well before the expected writing event, the students paused to process what they were learning about these natural events that shape the Earth. Over two days, groups of three learning partners created large drawings to show their understandings and misconceptions. The task was open-ended: Show what you know about fast and slow changes to the Earth’s surface.

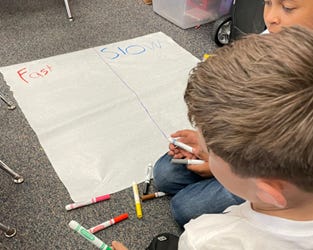

Independently, with no support from the teacher, discussions about organization of their ideas began. In their group of three, students discussed how to represent their learning in categories.

· “What if we put fast changes on one side and slow changes on the other?”

· “Maybe we can put three fast changes and then three slow changes?”

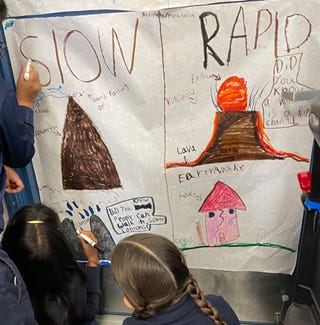

· “Let’s call it rapid changes instead of fast changes.”

On Day 1, partnerships planned the organization of their information about fast and slow changes and began to illustrate the changes.

Discussion then moved to considering what content to include in each category.

· “I’m drawing a canyon. It’s a slow change.”

· “When a volcano explodes, it’s a rapid change. But sometimes they are extinct so they don’t explode anymore.”

· “Floods can be fast and slow.”

On Day 2, partners added additional details to their drawings. Some added labels with arrows, included questions for their readers, and used illustrative techniques, such as lines and arrows, to indicate movement and cause and effect.

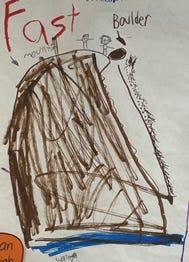

Misconceptions emerged, too, when they drew, as some learners attempted to understand and/or integrate new information with existing schema. These misconceptions had not previously emerged before this drawing experience, providing an important assessment opportunity. For example, erosion caused by wind and glaciers were both nearly inconceivable events to some of these young learners. In addition, winds that cause rocks to change brought tornadoes to mind for some of these novice learners. And, when the class learned about how sand forms when boulders in the mountains fall into rivers and break apart over the course of their journey to the ocean (a slow change), the initial video of a boulder falling rapidly down the side of the mountain was the image some learners held onto. Each of these misconceptions appeared in one or more drawings.

· “The rock is going slow down the glacier.”

· “Tornadoes are fast and they change stuff so they’re a rapid change.”

· “The boulder is going fast down the mountain. It goes so fast to the water that it splashes everywhere”.

Drawings capturing misconceptions about fast and slow changes to the Earth’s surface.

Over the next few days, after their drawings were complete, each group presented their illustrations to the class. As each group shared their understandings, the class identified and celebrated their ideas and openly appreciated the illustrative techniques used. In addition, misconceptions were explored and clarified, not as wrong ideas, but as opportunities for learning. Each time they explored an idea, accurate or not, the class thanked that group for helping everyone make their thinking stronger.

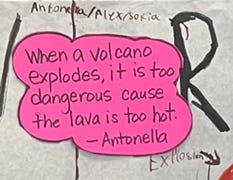

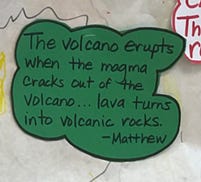

At the end of the unit, after each student completed their writing for a grade, I extended the learning one last time by taking a quote about the fast or slow change from each student’s composition. As I displayed each student’s quote (after explaining what a “quote” was!), that student read their quote to the class and was celebrated for what they knew and wrote. Finally, each quote was attached to the display of their illustrations. The layered classroom display allowed ongoing opportunities for students to revisit their learning through the language and drawings of the students themselves.

Quotes from 2nd graders about volcanoes

Our completed display of learning

Teacher decisions that affect the Conditions of Learning

Some decisions that supported a learning environment full of talking, drawing, and writing include:

· Working in a group of three. As the students worked with partners, their discussion allowed them to learn from and with others, a principle of Engagement. Working in groups also created a safe space for engaging with the content and showing your learning. In addition, working with others strengthened Expectations students had for themselves and others, as each learner participated and contributed to their group’s illustration. After this experience, Jaelyn took Responsibility for her own learning when she requested partnerships going forward include three students because she learned so much more from having two partners rather than just one (we usually had learning pairs, rather than trios).

· Drawing their understandings before they write. Crafting their illustrations with partners provided multiple opportunities for students to take Responsibility for showing their learning. Deciding what information and ideas to include and how to include it shows a strong Response to the content they’ve learned. Determining how to engage observers of their work through the kinds of writing and text features they include with illustrations shows Responsibility for themselves and Expectations for other students as meaning-makers.

· Creating a layered display of illustrating and writing. In a world of classrooms filled with teacher-created or commercially-produced charts and individual student work products, this creative expression of learning—of extended talking, drawing, and writing—is a demonstration of how an artistic, productive learning environment reflects both the collective understandings and the individuals in a classroom. Every student contributed to the overall creation; their Employment was successful. Responses from peers to their illustrations affirmed each group and, yet, the individual members of the group were acknowledged as well (most groups enjoyed pointing out who contributed various parts of the drawing). Finally, because the creation occurred over multiple days and learning experiences, opportunities to reframe misconceptions as approximations abounded; learners were able to view misconceptions for what they are—opportunities to think and talk your way to meaning.

Try this out

· Alone or with colleagues, look across your lesson plans from the past month. How did you incorporate talking and drawing to strengthen learning experiences? Can you identify places where you included or could have included talking and drawing to strengthen learning experiences for your students?

· With a group of colleagues, visit each other’s classrooms and discuss the learning environments. How do the environments reflect the collective learning of the class and the individuals as well?

· What kinds of creative expressions of learning are represented in your students’ learning experiences? Can you envision ways to include creative expressions of learning?