Setting Up the Classroom Library with Children

Learning is a consequence of thinking.

David Perkins, Making Learning Whole: How Seven Principles of Teaching Can Transform Education

How many of us grew up reading the cereal box at breakfast? And relished finishing our seatwork so we could select the latest color-coded card at our level from the SRA reading kit? And excitedly anticipated the weekly visit to the school library (yet suffered the ‘one-book-per-week’ limit!)? The reading lives many of us led in and out of school, and the associated thinking and learning, was too often dictated by the limited resources at hand.

If we want children to think of themselves as readers (and as thinkers and learners), they must be able to choose interesting, memorable books they find great joy in reading. To this end, classroom libraries play a significant role in the literate lives of children. Educator Regie Routman (2024) reminds us that being able to access books that “reflect the beautiful, complex, and multifaceted diversity of being human” is often for children the “first glimpse of what might be possible and who they might become in their present and future lives.” Living in a classroom with a rich and relevant library offers children opportunities to develop reading “habits,” those behaviors which define life-long readers: choosing books they love, sharing books with others, and reading books “as one would breathe air, to fill up and live” (Dillard, 2013).

But, strong classroom libraries don’t happen by chance; they are the result of intentional decisions about the social, emotional, physical, and intellectual facets of learning and teaching that surround the library. But, here’s the clincher—those decisions can’t be made just by the teacher.

Into the Classroom

To invite children into the decision-making process when setting up our library, the 2nd grade students and I discussed their ideas and feelings about the classroom library, using a series of questions designed to guide their thinking process.

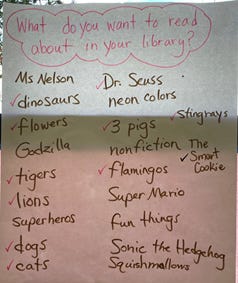

First, students responded to this question, What do you want to read about in your library?

“Ms. Nelson.”

“Dinosaurs.”

“Flowers.”

“Godzilla.”

“Tigers.”

The list was extensive with no slow-down of ideas. They had definite opinions on what they wanted to read. And, since every teaching opportunity is also an assessment one, I reflected on what their thinking revealed about this community of learners and what it might mean for future teaching decisions.

· Their list shows an awareness of some book characters (e.g., Ms. Nelson, The Three Little Pigs, Godzilla, and Sonic the Hedgehog). Many are from games or videos, rather than texts. What reading experiences would introduce the children to other characters they would come to love ?

· Many nonfiction topics are interesting to the students (e.g., dinosaurs, lions, tigers, dogs, cats). What initial topics would we begin with? What else might we explore?

· Only one author made the list (e.g., Dr. Seuss); this was after a probing question, “Are there any authors you’d like to read?” Introducing children to authors will be critical, for reading and for writing. What authors will become our mentors?

· Only one book was named by title (e.g., The Smart Cookie). This was the last idea offered. Learning to identify and discuss books they love will be important to their reading and writing lives. What books will we read together to “fill up and live” within their hearts and minds?

During the following two days, we used a modified version of Compass Points (2019), a Thinking Routine from Harvard’s Project Zero, to explore their ideas and opinions on the library we would be creating together. (The existing classroom library had an extremely large number of books on several shelves but without any discernable organization.) This Thinking Routine uses four questions to investigate student thinking about a topic, one for each compass point, N, S, E, and W. We used the questions in the order suggested by Project Zero, spacing the discussion over two days.

The first day, students responded to these two questions: What do you need to know about our library? and What excites you about our library? The words of the few students who spoke reflected some interest and excitement; most students were quiet and didn’t contribute. The overall tone of the discussion seemed to reflect a hesitancy, as though they were unsure of their role in this process; I wondered how much experience they had in giving input on how a classroom might work.

The following day’s first question elicited much more thinking, however: “What worries you about the library?”

· “We won’t have enough time to read books.”

· “What if we don’t like the books?”

· “What if we mix up the books?”

· “The books might get damaged.”

These concerns revealed ever-developing reader “habits” as the children named ongoing dilemmas all readers face: finding time to read in books they choose and caring for books which are available to them (what adult reader doesn’t need more book shelves!). Again, I wondered about their prior experiences in making decisions for their own reading lives and what it meant going forward.

The second question on this day, “What suggestions do you have for our library?” brought forth an extensive list of design qualities the children envisioned for their library: lights, blankets, pillows. While this was the last question, this was the first question that hinted at ownership of the library; the physical space they imagined was personal—comfortable and inviting. These responses reflect the emotive “habits” associated with being a reader; I felt their joy and excitement, no doubt from previous experiences in classroom libraries.

Using their suggestions, we designed the library to be cozy and inviting. It became a well-loved, well-used classroom space.

Teacher decisions that affect the Conditions of Learning

· Creating a dynamic classroom library with children, nor for children. Teachers spend extraordinary amounts of time and energy creating classroom spaces, including libraries, for children. Involving children in the process of creating the library together supports student engagement as they see themselves as “doers” (in this case, “library users” and “readers”). Children take responsibility for how the library operates, increasing the likelihood for their employment of the library itself. The classroom library belongs to the community, not the teacher.

· Taking time to explore concerns as well as wishes. Concerns are embedded in the expectations children have for learning—whether they believe in themselves as learners. Addressing these expectations leads children to feel safe and free from any harm, a principle of engagement. These discussions support learners to take responsibility for their reading lives as they make their worries, along with their preferences, known.

· Reflecting on their responses to guide instruction. A teacher’s response to what children share is directly related to student engagement. The insightful thinking by these 2nd graders led to a series of lessons about organizing and using the library and caring for books to address their concerns. As the library evolved across the school year, it reflected many of their early ideas, wishes, and concerns about book choice, time, organization, and design, which directly led to strong reader “habits.” Each teacher decision based on student thinking strengthened the learning that was possible. And that is what putting the Conditions of Learning into place is all about.

Try this out

Use these questions to think for yourself or talk with your colleagues about setting up classroom libraries with children.

· How do you set up the classroom library? Do you involve students? In what ways?

· What discussions do you initiate that invite students to explore their thinking and feelings about the classroom library? What do you learn as you reflect on these discussions?

· How do you ensure the library reflects the reading preferences of the students in your classroom?

· How do you provide time and opportunity for your students to communicate and problem-solve with you and the class regarding the classroom library?

Hi Debra, I am moving back into a grade 2 classroom role (after 20 years of RR/1-1/small group literacy intervention teaching or teacher mentoring) and will be using this -and many of your other teaching suggestions - to help me set up my classroom/kiddos/myself for success!

I also want to say a huge and heartfelt “Thank you!” 🙏for all your posts and wisdom! I am so looking forward to hearing you speak at our next MTS PD day (with MELIT) in October! -Marnie