Learning to Read Like a Writer

Reading and writing help us take the blinders off so we can look around and say, “Wow”…

Anne Lamott, Almost Everything: Notes on Hope

In Almost Everything: Notes on Hope, Anne Lamott’s chapter on writing begins with her typical unvarnished honesty, laced with humor. Writing, she says, “almost always goes badly for everyone, except for Joyce Carol Oates.”

Anne’s words of wisdom about the power of writing (and the reading that supports it) illuminate the bond between writing and life and hope. No matter the writer’s age, Anne reasons, writing gives us perspective that increases our reverence for life itself. “Reading and writing help us take the blinders off so we can look around and say, “Wow,” so we can look at life and our lives with care, and curiosity, and attention to detail, which are what will make us happy and less afraid.” She encourages writers to be curious and pay attention, essential habits for both leading rich lives and for writing. The wonderful news for teachers: these beliefs about writing apply equally to grown-ups and children.

Anne goes on to reveal a great “secret” of writing that she shares with adult audiences as well as her grandson’s first grade classmates. The “secret” to writing? Keeping one’s butt in the chair (she confesses when she uses the word “butt” with first graders, their laughter is how she knows she’s got them paying attention, which, as it turns out, is ninety percent of writing). For those of us who teach young writers in our own classrooms, we know how hard it is for kids to “keep one’s butt in the chair,” to persevere when writing doesn’t come easy, when the voice in one’s head says “I don’t know what to write about” or “I’m done.” Our role is to make sure writing happens every day for kids so they get the opportunities to be writers, ones who learn what to do when the choruses of “can’t” and “don’t” arise.

In the story of fiction writing instruction that follows, the students and I study writer’s craft techniques for the first time. We would be learning to “read like writers” (Smith, 1988) using a 5-part structure devised by Katie Wood Ray (1999), later revisited by Carl Anderson and Matt Glover (2024).

In preparation for this unit, we reread several well-known texts we had enjoyed together, refreshing our thinking about these favorites before commencing our study of craft in these texts. (You can read about a conference I had with one student during this unit in an earlier post here.) Some of the well-known texts we re-immersed ourselves in were Dogzilla and The Paperboy by Dav Pilkey, Chrysanthemum by Kevin Henkes, Harold Loves His Woolly Hat by Vern Kousky, Matthew and Tilly by Rebecca C. Jones, and Quiet Please, Owen McPhee by Trudy Ludwig. Each of these texts offered examples of writer’s craft that would be especially important for supporting these young fiction writers to move past “I’m done.”

Into the Classroom

To introduce the concept of learning to make our writing better, I shared that writers have to change their thinking from “I’m done” to “What can I do to make my writing better?” One day, Alejandro caught himself as he began to utter, “I’m d-” He paused, smiled, and said, “I’m finished!”

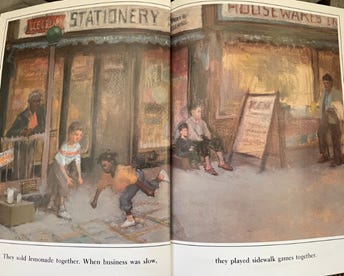

After defining writer’s craft as “what writers do to make their writing good” (Ray, 1999), the students and I began to revisit the known texts to notice things the author did as a writer. Ray suggests a series of steps to guide students through the process of reading like writers (Step #1: “Notice something about the craft of the text.”) In the first text we explored, Matthew and Tilly (a delightful story about two friends and the ups and downs of their friendship), students talked initially about what the characters did together and then how the characters called each other names during a fight.

These ideas are what Ray calls “readerly” things (i.e., general feelings that the words evoke in us as readers). To nudge the students to notice the “writerly” things (i.e., words, how writers put words together, or how they structure a text), I first named their “readerly” thinking.

“Oh, you’re thinking like a reader. You’re noticing things about the characters and how they feel.” To get to the writerly thinking, I probed, “How did the author help us know Matthew and Tilly like each other? Let’s look back and see if we notice any words she used to help us know Matthew and Tilly like being with each other?” On this reread, students noticed a repeated word used by the author throughout the book that helped them know about Matthew and Tilly’s friendship—the word together.

Step #2 in this process asks readers to put themselves in the mind of the writer (“Talk about it and make a theory about why a writer might use this craft.”). I said, “A writer can choose any words to use when they write. Why do you think an author might choose to use the same word over and over in a book?” Ultimately, students thought an author might choose to use the same words over and over so readers would notice this word, think it was important and maybe help them understand something important (e.g., being together was better than being apart).

Step # 3 asks writers to “give the craft a name”; we called the craft we had noticed “repeat important words or details.” By this point, we were also discussing craft as a decision a writer makes.

Step #4 asks us to “think of other texts you know. Have you seen this craft before?” We noticed many authors make this exact same decision in their writing so we think about important things! For example, in Chrysanthemum, author Kevin Henkes repeats both words and actions (e.g., “Chrysanthemum, Chrysanthemum, Chrysanthemum”)—Chrysanthemum loves her name so much. In Harold Loves His Woolly Hat, author Vern Kousky repeats words and actions, too (e.g., Harold tries to trade different items to get his hat back from the crow)—Harold really wants his hat back!

Step #5 asks writers to “try and envision using this crafting in your own writing.” Ray uses a frame to support students in this envisioning process: “So, if I am writing and I want to ___, then I can use this technique.” In my lesson, I said, “If I’m writing and want to share something important and help readers notice something important, I can find places to repeat important words or actions across my story.”

To demonstrate envisioning and using this craft technique, I chose to revisit a fictional story I’d written about my kitty, Fiona, who runs away from home, thinking she wants to live with a different family so she can always get her own way (but, of course, comes home in the end). As I reread my story about Fiona, I thought aloud about how much Fiona and I loved each other and what important words I might want to use over and over to show this thinking (meaning determines the craft technique, not the other way around). I decided repeating the word “loved” in the beginning of the story and later at the end showed this was an important idea in my story. After I modeled rereading my story to decide how and when to use this craft technique, students reread their own stories and talked with partners about important words or details they might repeat in their stories and why (it’s important to note that writers are not required to use any technique we discuss; writers must make the decision for themselves to use a craft technique or not). Aiden and Alejandro were two students who decided to use the craft technique, repeating important words or actions, in their own writing.

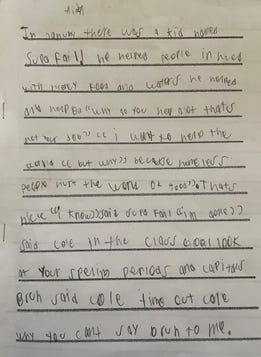

Aiden decided to repeat the word “helped” in several sentences in the story’s introduction to show important information about his character.

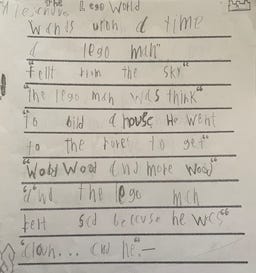

Alejandro decided to repeat the word, “wood,” in this sentence: “He went to the forest to get wood, wood, and more wood…” When Alejandro read this sentence to me, he said, “I repeated the word three times so readers would know it was a LOT of wood he got.”

Teacher decisions that affect the Conditions of Learning

The most important goal underlying the “reading like a writer” process Ray articulated is for students (and their teachers) to understand writing is a process of decision-making. Teaching decisions that affect the Conditions of Learning set up students to be decision-makers.

· Revisiting known text to study writer’s craft techniques. When children are immersed in quality literature and teachers study those mentor texts for elements of writing craft, the demonstrations teachers provide are relevant and holistic in nature. It’s this ‘wholeness’ that contextualizes the craft technique and allows students to see the meaningful and purposeful effect of the craft. So, to help students write well, it’s critical that teachers find “texts that have writing in them that matches the kinds of meanings our students are trying to convey” (Ray, 1999).

· Supporting students to notice what writers do that make their writing “good.” Beginning a craft study by asking children what they notice a writer did in a text is constructivist teaching at its finest. Responsibility for noticing is handed over to students, communicating an expectation they are noticing kinds of thinkers. And, once the craft technique is identified and discussed, taking time to look for this same craft in other texts again communicates an expectation that students are capable learners. Since experienced writers use the same kinds of crafting techniques, if we want our students to write well, they will need to learn how to learn from other writers.

· Noticing both readerly and writerly things in student discussions. How teachers respond to a student’s approximations when talking about writer’s craft is critical. If students respond in a more readerly way, honoring their thinking by labeling it “readerly” helps students learn the difference between readerly and writerly noticings. Responding in this way also strengthens the teacher-student relationship that underlies student engagement. In addition, as teachers probe further to get at the writerly craft technique under discussion, they communicate their expectation that students can do what Ray calls this “writerly kind of noticing.” Ultimately, noticing craft becomes “almost automatic and will be the first thing you do when you become proficient at reading like a writer” (Ray, 1999).

Try this out

Use these questions to think for yourself or talk with your colleagues about teaching children to learn to write from other writers.

· What texts might you use to study writer’s craft techniques?

· Look at your favorite children’s books. What writer’s craft techniques are you familiar with already? How might you support yourself to learn more about writer’s craft?

· How might you integrate Ray’s 5-step process to learn to read like a writer into your existing writing units?