Assessment for Learning

“Formative assessment should not merely focus on academic learning, but should include the conditions for community learning.”

Peter Johnston, Opening Minds: Using Language to Change Lives

Formative assessment of the social aspects of learning, those conditions for community learning to which Peter Johnston refers, is tricky. If formative assessment is about finding strengths, what does one look for to understand how relationships and other aspects of community are developing and evolving? How will a teacher even go about gathering evidence? And, once we do get a sense of the community dynamics, what does it mean for our teaching practices?

In the story that follows, I share an experience which turned out to be an important assessment of the community that surrounded the third graders I was learning alongside. The students and I both wanted them to choose their own partners for independent reading. But what I didn’t realize going into this experience was just how much I would learn about the social aspects of this community of learners.

Into the Classroom

Can we choose our new partners? Please…

What began as one voice soon became a chorus—I’d just shared the need to form new partnerships for independent reading and previous partnering fueled this current enthusiasm. During our just-completed poetry unit, students had frequently partnered and re-partnered themselves informally to share their writing. The request was serendipitous, as I, too, had been considering ways to involve students in forming their own partnerships. At the same time, I was also thinking about how to strengthen students’ collaborative abilities with these new partners and support them to reflect on their own learning process.

Even though students would choose their partners, I knew I needed some say in the matter, too. While partnering by levels is not conducive to learning (Scoggins and Schneewind, 2021), I also knew some partnerships would need a bit of gentle shaping for other reasons (i.e., students had varying needs for language support; a few students were frequently absent; a couple of students received resource support during this time). To provide this additional support, these new partnerships would have three members, rather than pairs of students.

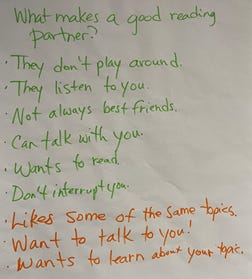

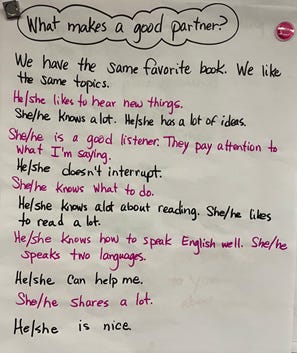

I designed a series of lessons to offer students (and me!) time to think and reflect on the social aspects of learning while they chose partners. Our first lesson reflected on what makes a good partner. These students had worked in partnerships before, some successfully, others, not so much, so this reflection was shaped by and honored their previous experiences. The chart below was created during the opening portion of reader’s workshop; what is in green font was elicited before they began to read independently.

Our first reflections on partnerships.

Each response, while valid and important, felt a bit teacher-focused, as though the kids were echoing what they felt a teacher would want to hear. For example, the first response, “they don’t play around,” was immediately couched with “yeah, they’re doing what they’re supposed to be doing.” Beyond this first idea, extended pauses ensued as students wondered what else to suggest.

Wanting to augment this thinking, I observed students’ interactions with partners during independent reading that day. Alberto was overheard telling his partners “I really liked this book because...” Mia excitedly shared with her partners how her book has similar words at the end of the book that were found at the beginning (“See, it says it right here.”) Aniyah and Valentina chose to read a book together, taking turns reading aloud to each other.

During the share session at the end of reader’s workshop, I named what I’d noticed students talking about and doing. As I added these noteworthy actions to the chart (the ideas recorded in orange font), I reflected that these might also be things to consider when determining who might make a good partner.

The following day, I explained the purpose of the list they were to make that day.

“Today, you will make a list of five people you think would be good partners for you and why you think they would be good partner. I’ll use your suggestions to put groups of 3 partners together. At least one of your partners will be someone from your list. I want you to be able to choose your partners… and, as your teacher, I also have to think about how some of us need more support for language—some of us have more Spanish than English and others have more English than Spanish, right? So I’ll also be thinking about that as I form the partnerships using your lists. I want to make sure you have a partner you want and a partner who can support you with English or Spanish if you need it.”

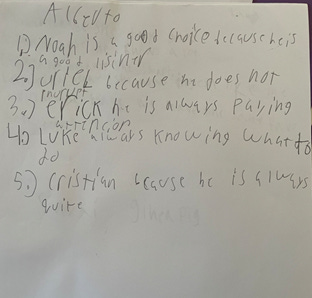

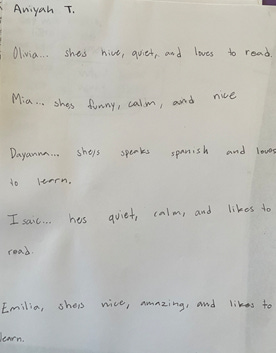

Alberto and Aniyah listed their five choices for partners and why they think these would be good partners.

In cross-checking their suggestions to form partnerships, the unexpected assessment data about the learning community surprised me. Here’s what I learned from the reasons they gave for classmates they chose:

I learned what they know and appreciate about their classmates. It was heart-warming to read what they knew and felt about each other. And, as I read, I could see they had more expanded thinking about what makes a good partner than they’d initially shared. To share this with the students, I created a new chart of characteristics of good partners using the students’ own words. While some ideas are similar to the first chart (we compared them), hearing their own words reflected back to them strengthened and extended their thinking about partners and themselves.

The second chart created using student’s own words.

I learned whose voices were valued by other students and why. A few students appeared on multiple lists. For example, many students wanted Luke as their partner because “he knows everything about reading,” “he always knows what to do,” and “he can help me.” Uriel was listed several times, too, because “we have the same favorite book,” “he doesn’t interrupt,” and “he shares a lot.” These ideas show respect for their peers.

But I also learned whose voices weren’t valued (yet!). A few students weren’t included on another student’s list. This gave me pause as I considered how those students, those who tended to be quieter, less confident learners, were viewed by their peers.

******

I hadn’t gone into this experience of students choosing partners considering it an assessment of the learning community but afterwards I realized it clearly was. First, having students suggest partners and their reasons for doing so revealed who has an understanding of what to consider when choosing collaborative partners. Students didn’t just name friendship as criteria (although some did); some recognized how someone else can actually help you learn. This is a crucial understanding for an effective learning community (Johnston, 2012). Their lists also revealed an awareness of the strengths of other learners in the community and what those students bring to a partnership. And, importantly, it revealed that some students are overlooked by their classmates as possible learning partners, a true loss of potential. These social needs require support right alongside the academic lessons we would experience.

So based on what I learned through this unforeseen assessment opportunity, over the next few weeks, we would need to focus on:

Shifting the way some children are viewed by other learners (and possibly for themselves, too). My language throughout lessons needed to be process-oriented (noticing and naming the strategic actions of the students) and emphasize collaboration, not competition.

Supporting the challenges of working in groups of three. In collaboration, all voices need to be heard for the most powerful learning to occur. Recognizing when issues are occurring (e.g., such as when one partner isn’t participating or when one partner is dominating the conversation) and considering ways to resolve the problem still needed attention.

Elaborating on what purposeful talk is and consider ways to engage in this talk intentionally. While students had broad ideas on what they might talk about with partners, I needed to be more explicit in noticing and naming what literate thinking and talking sounds like and support this during independent reading.

Teacher decisions that affect the Conditions of Learning

Assessment of learning for the social part of the classroom community is just as important as academic. Some decisions I made during this experience that affect the Conditions of Learning include:

Listening to students. When we listen to students, they show us what they need for learning; this is the basis of formative assessment. When the Conditions are in place, they provide a context for this to occur. For example, the relationships between and among the learners and a teacher are the basis for Engagement. Students who believe they won’t be harmed for attempting learning are more likely to Approximate which offers teachers opportunities to learn what students understand and what they need next for their learning. In addition, trusting students to choose partners offers them Responsibility necessary for any learning to occur.

Building in time to reflect. Reflection empowers learning and is tightly connected to all the Conditions of Learning. When teachers ask students to reflect, they make clear their Expectations of learners as capable individuals; these reflective moments also affect the Expectations children have for themselves. A teacher’s Response to their reflections also builds trust, again strengthening Engagement.

Basing next teaching steps on assessment. Our Response to what learners reveal through our assessments is what connects teaching and learning. In a constructivist classroom, this kind of Response to assessment data (i.e., our use of specific, strategic language within teaching) makes the Immersion and Demonstrations we provide relevant and meaningful. Teaching is aligned with learning and more likely to be effective. And that, really, is the point of any assessment, right?

Try this out

How do you partner students for collaborative learning experiences?

What are ways you learn about the community you build and extend? What assessment opportunities or tools do you use to find out about the strengths of the learning community?

How do you plan for teaching using the assessment data about the community’s strengths and needs?